We might be happier than our poorer neighbors, but not happier than our poorer grandparents at our age, why?

- The Easterlin Paradox

The notion, "Money doesn't buy happiness", might not feel intuitive to many. We feel happier when we get a raise; and in general, people who are financially better off seem happier than their poorer neighbors in the same city, or even in the same community.

Researchers also has data showing that, cross-sectionally, happiness increases with income level, whether it is within a country, or between countries.

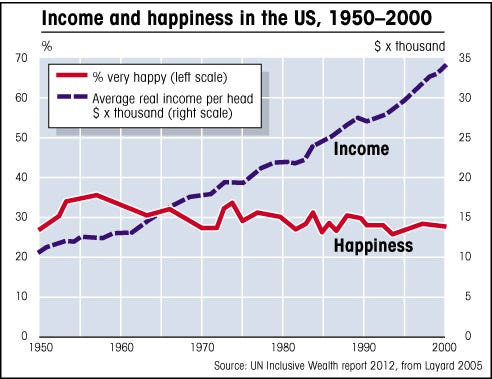

However, if we compare between generations, or over time along the history, the data show a different picture. See the chart below, for example.

Data from other countries, especially developed countries, show a similar pattern.

So, we are on average much “richer” than our grandparents or even our parents; but are we happier? Not at all.

Why not? Why does our happiness level stay essentially the same over many decades despite “real income” (inflation adjusted) has more than tripled, in the US and similarly in many other countries?

Why is that on the one hand, happiness increases by income level at a given time as some data showed, but on the other, our happiness hasn’t increased at all for generations while our income level has greatly increased?

Richard Easterlin, the first economist to study happiness data while a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania in the 70’s, first identified this phenomenon which later named Easterlin Paradox or Income Paradox.

An explanation provided by Easterlin is that one's feeling of happiness depends on comparison between their income and their perceptions of the average standard of living. That is to say, increased income brings increased happiness when compared to a certain perceived average standard of living. Over time, however, as the whole society’s income level increases, the perceived average standard of living also increase at a similar pace, leaving no net effect on happiness.

There might be other reasons that could explain this paradox, as some described in the late legendary Dr. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s article, “If we are so rich, why arn’t we happy?”. These reasons included: Adaptation, that we get used to the upgraded lifestyle from the increased income fairly quickly, diminishing the happiness from such increase/upgrade; Escalation of expectation, that we expect more after reaching an income level; And changing of reference group, that higher income may lead to changes of reference group in social comparison. More detailed descriptions of these reasons could be found in another post here: Why Does the “Happiness” That Comes with More Money/Material Possessions Do Not Last for Long?

These later reasons indicate that the “disappearance” of happiness from higher income does not just happen between generations or over time, it could happen in everyone’s life at the present time. As professor Easterlin suggested, one's increased income gives only a “short boost” to their happiness, but when one realizes that the average standard of living has also increased, the “happiness boost” produced by increased income disappears.

So, it is not the income, but our perceptions (of living closer to or above the average income, of living better than our neighbors, etc) that bring us the often short-lived “boost of happiness”. The perceptions may change with changes such as in the average living standard or in comparison groups.

This may support “money doesn’t buy happiness” (It’s our perceptions that “buy” it, but only briefly). More importantly, it shows that pursuing income increase (at the personal level) or economic development (at the country level) might not be the effective route to happiness, especially in developed countries where basic needs have been fulfilled for most people.

That leaves the question for each of us: What is the effective route?

Join us to explore the answer(s) in this substack!